Artículos de revisión

The relationship between international trade and immigration policies: Evidence from Mexico and the United States La relación entre el comercio internacional y las políticas de inmigración: evidencia de México y Estados Unidos

La relación entre el comercio internacional y las políticas de inmigración: evidencia de México y Estados Unidos

The relationship between international trade and immigration policies: Evidence from Mexico and the United States La relación entre el comercio internacional y las políticas de inmigración: evidencia de México y Estados Unidos

Cuadernos Latinoamericanos de Administración, vol. 16, núm. 31, pp. 1-16, 2020

Universidad El Bosque

Recepción: 21 Julio 2020

Aprobación: 09 Octubre 2020

Abstract: This paper is concerned on how the Trump administration treats Mexico as testing ground in terms of trade and immigration, two major subjects on which the US president promised a radical policy shift. The main objective of this paper is to demonstrate that the announcement of the new immigration law, known as the Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment (RAISE), and the immigration policy as a whole are the reflection of racism and white supremacy of the Trump administration. We analyze how the current account deficit between Mexico and the United States has been used as an anchor for the immigration policy, and also, we analyze the realistic theory of international relations, according to which, power is at the center of all types of free trade agreements. According to these analyses, we point to the next structural problems: (i) the racism and white-nationalism in the Trump administration, (ii) the causes and consequences of power and the degree of exploitation in the trade relationship between Unites States and Mexico, (iii); that the trade deficit reduction of US with NAFTA partners is not a reflect of Fair Play in a World Trade and, therefore, is unsustainable in the long term, and (iv) that the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in the first quarter of 2019 (3.2 percent) of the United States is not the measure of the economy or import tariff, it is a result of a big corporate tax cut which necessarily mean a higher corporate benefits.

Keywords: Trade deficit, Wages, Power, white nationalism.

Resumen: Este artículo describe cómo la administración de Trump trata a México como un campo de pruebas en términos de comercio e inmigración, dos temas importantes respecto a los cuales prometió un cambio radical de política. Así, el objetivo de este trabajo es demostrar que el anuncio de la nueva ley de inmigración, conocida como Reforma de la Inmigración Estadounidense para un Empleo Fuerte (RAISE, por su sigla en inglés) y la política de inmigración en su conjunto son el reflejo del racismo y la supremacía blanca de la administración Trump. Se analiza el déficit en cuenta corriente entre México y Estados Unidos, que se ha utilizado como ancla para la política migratoria. Asimismo, se destaca la teoría realista de las relaciones internacionales, según la cual el poder está en el centro de todo tipo de acuerdos comerciales liberados. Dado lo anterior, se señalan los siguientes problemas estructurales: (i) el racismo y el nacionalismo blanco en la administración Trump; (ii) las causas y las consecuencias del poder y el grado de explotación en la relación comercial entre Estados Unidos y México; (iii) que la reducción del déficit comercial de Estados Unidos con los socios del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte no es un reflejo del Juego Limpio en el Comercio Mundial y, por lo tanto, es insostenible a largo plazo, y (iv) que el crecimiento del Producto Interno Bruto (PIB) en el primer trimestre de 2019 (3,2 %) de los Estados Unidos no es la medida de la economía o el arancel de importación, sino el resultado de un gran recorte de impuestos corporativos para que este sector logre mayores beneficios.

Palabras clave: Déficit comercial, salarios, poder, nacionalismo blanco.

Introduction

Immigration and trade are now at the forefront of the United States (US)-Mexico debate. By hearing the term NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) many readers think that the economic relationship between US, Mexico and Canada is good with respect to economic integration. However, the process of political and commercial relations between Mexico and the US have been, and will always be, relations based on power imbalance. During the last years, the Mexico-US border is witnessing commercial and migratory conflicts like never before. In this perspective, Donald Trump is pledged to rewrite the NAFTA, and has referred to it as “one of the worst trade deals ever made”.

In addition to the economic dimension, the immigration issue between both countries was crucial in the 2106 presidential campaign of Trump. To understand and contextualize the immigration policy of Trump, it is important to analyze his election in a context of white supremacy. In his presidential announcement speech campaign, Trump threats towards Mexico have been increasing. For him, Mexico is the real border problem of US security. In June 2015, he mentioned that: “They’re sending people that have lots of problems and they’re bringing their problems”, he said. Additionally, he claimed: “They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists, and some I assume are good people, but I speak to border guards and they tell us what we are getting”. He promised that, as President Trump, one of his first actions would be to build a “great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall” (Time Staff, 2015). We will be discussing this in the next section.

Some theoretical approaches to international trade and immigration policies

Over the past three decades, international trade and immigration has risen in prominence as a tool within social phenomena. White and Tadesse (2010) present a view of immigration and international trade in a sense of cultural diversity. At the same time, they offer a detailed understanding about how immigrants increase trade flows by exploiting superior information regarding host country markets and home country markets and/or by acting as conduits that bridge cultural differences between their host and home countries.

Christina Boswell (2010) describes some additional characteristics such as “pull factors”, international migration and forced displacement. She notes that: “In the case of economic migration, push factors would typically include economic conditions such as unemployment, low salaries or low per capita income relative to the country of destination. Pull factors would include migration legislation and the labor market situation in receiving countries” (Boswell, 2010, p. 3).

It is important to bear that several researchers analyze the discussion of racism and white supremacy of Trump’s campaign under different approaches. According to Inwood the “Trump’s rise to political power in the context of a white counter-revolutionary politics that emerges from specific geographic configurations of the US racial state and historical trajectories of anti-Black racism” (Inwood, 2019, p.580). The view imparted on his campaign speech (and his presidency) may be further explored in order to shed light on his intention of racism and white supremacy policies (Harkinson, 2016), which will need to be considered later on.

Guess (2006) introduced another perspective, arguing that: “Racism by consequence then is reflected in differential educational opportunities, economic differentials between whites and non-whites, residential segregation, health care access, and death rate differentials between whites and non-whites” (p. 652). This is especially true if we consider the income and wealth gaps between white and nonwhite households and the decrease of the net government expenditures for nonwhite people.

By contrast, Feagin analyses the term white supremacy through another approach. He points out that

the term White supremacy emphasizes an ideology of White superiority and reflects the creation of “White” and “Black” identities by the White founders of this Nation. The all-encompassing phrase I prefer is systemic White racism. This phrase refers to the system of racist domination and oppression and its consequent racial inequality that has been created, maintained, and legitimized by those who subscribe to the White supremacy ideology. (Feagin, 2012, p.79)

Both the policies and ideology of the Trump administration have been shown in practice and in speech to a high degree of discrimination and have inspired violence such as El Paso shooting in August 3, 2019, that killed 22 people (Schaefer & Baldas, 2019). Recent events such as completion the border wall with Mexico, restriction of legal immigration, reducing the number of asylum seekers, is what Feagin (2012) called: “white racial frame”.

As we can see, added to the already white counter-revolutionary, Maskovsky (2017) presented a view of “white nationalist postracialism”. The basic philosophy behind this approach is “the paradoxical politics of twenty-first-century white racial resentment whose proponents seek to do two contradictory things: to reclaim the nation for white Americans while also denying an ideological investment in white supremacy” (Maskovsky, 2017 p. 433).

The research question is whether or not Trump's immigration policy contributes to reducing the deficit on the balance of trade, this is a question that is often missing in the literature. To overcome this problem, we analyzed approaches from different scholars. Girma & Yu (2002), Peters (2017), and Clausing (2019) document the importance of Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and the immigration issue. Hoppe (1998) has observed the existence of elastic substitutibility between immigration and FTA, where “(rather than rigid exclusivity): the more (or less) you have of one, the less (or more) you need of the other” (Hoppe, 1998, p. 224). As Papadimitriou points out (Kregel, 2019):

The rise of nationalist political movements and governments has been partly abetted by a sense of conflict between the forces of globalization and mounting demands for national sovereignty in economic affairs. Increasing global market integration creates unstable dynamics that constrain national policy space, while calls for international cooperation or global governance structures to address these dynamics can themselves reinforce the impression of an erosion of national control, heightening domestic backlash. (p. 3)

The US-Mexico bilateral economic and trade relationship are facing tensions during the Trump administration. The 3145 km border that both countries share has known historical episodes of war, invasion, immigration, among others. When each country reached their independence, the United States grew at an accelerated pace through technology, strategic planning regarding the unification of the country, where each State retained its sovereignty, freedom and independence (Article II of the American Constitution), meanwhile, Mexico experienced an accelerated growth rate during the decade of the 40's until the mid-seventies with the implementation of the Industrialization model via Import Substitution.

[1] However, since 1970s’, Mexico experienced one of its worst crises in history, the well-known lost decade, where Mexican decision makers had to accept neoliberal measures, also known the Washington Consensus and the liberalization of trade by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as an important condition to reestablish Mexico's economic growth. Thus, the results of these strategies contributed to Mexico being able to settle the debts it had with US institutions. In this context, Ocampo (2014) noted:

The debt crisis of the 1980s is the most traumatic economic event in Latin America’s economic history. During the “lost decade” that it generated, the region’s per capita GDP fell from 112 percent to 98 percent of the world average, and from 34 per cent to 26 percent of that of developed countries. (Ocampo, 2014 p.1)

At the beginning of the 1990s’, under the IMF’s recommendations, Mexico decided to apply a commercial policy and financial liberalization with the objective of increasing exports, moving from an Import Substitution Model (ISM) to one of Export Substitution (ES). These strategies had some positive impacts on almost all macroeconomic variables. Furthermore, this period is often called the “export miracle of Mexico”, due to the export growth especially to the US market. However, it should not be forgotten that net exports are lower than gross exports, since the inputs needed to import to produce goods to be exported are more expensive. In addition, it must be mentioned that the majority of Mexican exports to United States are labor-intense goods not capital-intense goods. According to labor theory, there is a degree of exploitation in a trade relationship between developed and developing countries. As Cohen (1979) notes in his proposal Labor Theory of Value and the Concept of Exploitation:

the exchange-value of a commodity varies directly and uniformly with the quantity of labor time required to produce it under standard conditions of productivity, and inversely and uniformly with the quantity of labor time standardly required to produce other commodities, and with no further circumstance. The first condition alone states the mode of determination of value tout court.

The rate of exploitation = surplus value

variable capital

= surplus value

value of labor power

=time worked - time required to produce the worker

time required to produce the worker. (pp. 340-341)

United States Census Bureau, 2020.

The strategies applied during the first weeks of the Trump administration were the cancellation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and also requested Mexico and Canada to renegotiate the NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) as corrective measures of the imbalances of international trade in the United States. Under this perspective, the central problems Atkinson (2015) identified were that advanced economies faced increased competition from countries where wages of unskilled workers are lower is that he also promised the construction of a wall to prevent the passage of illegal immigrants from Central America and Mexico to the United States. From a political realism perspective, we can say that the Trump administration considers power and threats as the main means to achieve ends of any kind. It is important to mention that within the scope of international relations, the concept of power has been transformed during the last decades by the urgent need to solve common problems between countries. The analysis of power has been debated by several academics such as: Nicholas J. Spykman (1942), Reinhol Niebuhr (1959), Hans Mrogenthau (1948), George F. Kennan (1951), and Henry A. Kissinger (1957) in the United States during the forties. During the middle part of the 20th century, the concept of power has risen his prominence raison d’être in the international sphere and play a crucial role in the nature of foreign policy, thus, the search of power is identified as the struggle for survival. Consequently, Spykman’s approach of power is one of the most relevant contributions in the foreign policy realism. In this regard, Spykman (1942) mentioned: In the last instance only power can achieve the objectives of foreign policy. Power means survival, the ability to impose once’s will on others, the capacity to dictate to those who are without power, and the possibility of forcing concessions from those with less power. Where the ultimate form of conflict is war, the struggle for power becomes a struggle for war power, a preparation for war. (p. 17).

Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christian realism sounds much like Spykman on the domestic socioeconomic situation in the United States. We must engage in political action and in the use of power against others for we “cannot be good unless we're responsible, and the minute we're responsible, we're involved in compromise” (McKeogh, 2007, p. 201).

The premises of the realist theory are: a) the State is the most important element within a system “centered on the States”, b) the division of internal politics in relation to foreign policy, c) within an anarchic environment, international politics is a power struggle and d) there are levels of capabilities between nation-states. In addition, Morgenthau’s (1948) tough-minded foreign policy realism considers that international politics, like all politics, is a struggle for power. Whatever, the ultimate aims of international politics, power is always the immediate aim. Statesmen and peoples may ultimately seek freedom, security, prosperity, or power itself. Niebuhr’s (1959) though-minded foreign policy realism.

Under the assumption of power, Strausz (1942) considers that the international politics is dominated by the search for power and that during the history of mankind, the states fought to ensure or increase their power. That is why Morgenthau (1948) said that power is “control over the mind and actions of other men”. Affirmation that Holsti also implies when mentioning that “power is the general capacity of a State to control the behavior of others” (Holsti, 1964).

According to the realist approach in international relations theory, it is important to note that power is a three-dimensional phenomenon, there are some key components such as military and non-military, and within the last category we find elements such as: levels of technology, population, natural resources, geographical factors, political leadership, form of government, etc. All these components form a force of capabilities that can be used to maintain order within the international system. However, the concept of power in the 21st century has to be redefined in both the political and economic spheres under the logic of "Dependent States”[2]. In this regard, Select Committee on Soft Power and the UK’s Influence First Report (persuasion of power in the modern world) argues that:

The ability of military force alone to secure a nation’s interests has been recognized as facing increasing challenges due to the scattered and dispersed nature of modern conflict and war, including by the defense communities in the US and UK. […] this trend has several causes, including “the moral force of the concept of self-determination”, “the growing power of the people’s voice”, “the increasing trend for moral and political legitimacy to reside in the wishes of the people of a particular locality”, “the openness and global comprehensiveness of economic exchange and opportunity”. (par. 30)

However, during the foreign policy realism period and the Cold War, two important events have shifted the political economy in Mexico. First, the end of fixed exchange rates, which is the end of the Bretton Woods system. With the deteriorating position of the dollar, the international monetary system was thus changed, at least de facto, from one based on fixed exchange rates to one based on flexible rates. In this way, the postwar system of fixed exchange rates had become a casualty of reckless American policies, high inflation, and increasing international mobility of capital (Gilpin, 2000). Thus, in order to control inflation, the US government decided to increase the interest rate and the same time the rise in debt burden of Latin American countries, especially Mexico.

The second event was “the lost decade 1980” in Latin America and the risk of political instability, as a result of the of the Import Substitution Model (which was prevalent in 60s and 70s decades) This period refers to a significant decline in real GDP, also characterized by hyperinflation and unemployment. As a result, Mexico found itself in a situation where it was impossible to pay the external sovereign debt.

Thus, the need for a dynamic structural adjustment. A solution was eventually found in the Brady Plan, which given the rejection of default employed the natural response to a Ponzi financing profile, i.e. borrowing more to meet outstanding financial commitments. The over-indebted Latin American countries sought to create conditions in which they could attract the additional borrowing required to meet debt service (Kregel, 2004). So, the shift of the Import Substitution Model to the Export Substitution Model was required. Both United States and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) adopted some strategies based on Washington Consensus (WC), but more importantly the widespread adoption of trade and financial liberalization of Mexico.

Commercial and financial liberalization of Mexico

The Mexican economy needed to make some structural changes, major changes, in its economy structure in order to be competitive in the global market, which resulted in the application of a conventional (orthodox) model recommended by the IMF: “let capital flows and the economy will grow’’. In order to do that, it is important to have good market fundamentals, such as the implementation of contractionary fiscal and monetary policies. The objective of this has its starting point in the commercial and financial liberalization so that could help to reduce commodity dependence.

The policy of financial liberalization

The Mexican financial system was highly protected, with restrictions and regulated interest rates; the financial market was not up to the demands of the international economy. Therefore, it was necessary and non-extendable to modify some laws to establish the proper scenario for the development of the securities market and, at the same time, correct imbalances in public finances. For Álvarez and Azpeitia (2010), the Salinas administration had two basic objectives that the financial system had to fulfill: • Increase and channel national savings in an effective way to the most dynamic productive activities. • Expand, diversify and modernize the system to boost productivity and competitiveness of the Mexican economy. At the end of the 1980s’, Mexican government applied a neoliberal economic policy. This policy had its effects in several sectors of the economy, for example, financial liberalization was one of the points within the Washington Consensus (WC) that Mexico should comply with if the country really wanted to be competitive. Also, they were convinced that one of the problems that prevented the country from growing satisfactorily was, precisely, the lack of consolidation of a financial system incapable of generating sufficient resources for its development. The first point to notice is that, it was important to make the necessary adjustments to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), an important condition, although not necessary, for the economic growth for emerging countries. In this regard, this issue is emphasized by Joseph Stiglitz (2000): Foreign investment is not one of the three pillars of the Washington Consensus, but it is a key part of the new globalization. According to the Washington Consensus, growth takes place thanks to liberalization, "unlocking" the markets. It is assumed that privatization, liberalization and macro-stability generate a climate that attracts investment, including foreign investment. This investment produces growth. Foreign companies provide technical knowledge and access to foreign markets and open up new possibilities for employment. These companies also have access to sources of financing, especially important in underdeveloped countries with weak local financial institutions. (p. 96)

The financial liberalization strategy contemplates eliminating all legal barriers so that the country can receive capital from abroad. For this, it was necessary to modify the Foreign Investment Law (FIL) of 1973, which limited foreigners to a maximum participation of 49% of foreign companies in the country. According to Guillén (1997), “the Mexican authorities thought that this law contained very ambiguous definitions regarding which sectors would actually be subject to those limits, which allowed the discretional application of the norms” (p. 124). The result was that direct foreign investment rose from 3,175 to 10,972 million dollars between 1989 and 1994 (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, 2018). In addition, government took additional measures such as:

• Liberalization of bank interest rates. • Elimination of mandatory channeling of credit resources. • Substitution and subsequent elimination of the legal reserve and the liquidity ratio.[3] Through this financial liberalization, Mexico received many capitals from abroad. It must be said that the stock of American Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Mexico has substantially increased, not only quantitatively, but also in the diversification of this investment in almost all sectors.

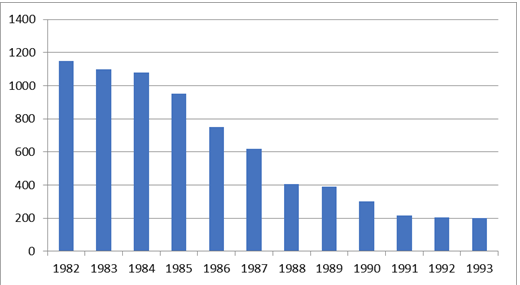

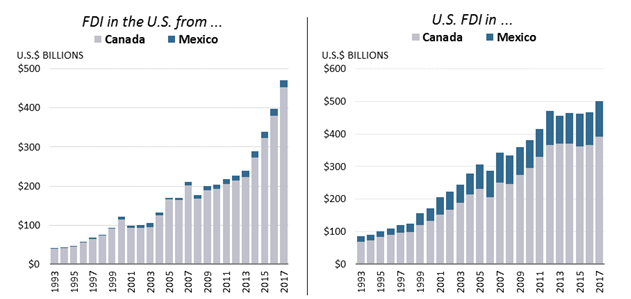

Figure 1

Foreign Direct Investment into NAFTA countries.

CRS based on data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

As we can see in figure 1, all these measures contributed to the flow of FDI in Mexico, specially from the USA. However, despite uncertainty about the outcome of the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, inflows to Mexico remained stable at $30 billion, supported by record-high investments into the automotive industry (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2018).

Trade liberalization

Mexico agreed to reduce import controls of tariffs when adhesion to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was ratified, in 1985. Between 1988-1994, this strategy intensified until the signing of the agreement: NAFTA, whose negotiations dealt with points such as the ones mentioned below: • Encourage investment and trade in goods and services through the gradual and complete elimination of tariffs. • Eliminate o

r reduce to the possible non-tariff barrier, such as import quotas and permits and technical barriers to trade. • Establish effective protection mechanisms for intellectual property, patents, trademarks and trade secrets. • Promote expeditious mechanisms for the solution of disputes. (Sandoval & Arroyo, 1990, p. 230). The liberalization of economic policy also had a tremendous impact on the manufacturing sector. It is important to mention at the early nineties; trade liberalization was almost complete in this sector due to the oil crisis of 1986. The percentage of participation of the manufacturing sector in total exports was insignificant, around 21.1% during the first three years of De la Madrid administration. Due to the fall in the oil price of 1985-1986, it was necessary to change the strategy of “petrolization”, or “petrodependence”, of Mexico towards a diversification of products that could reduce Mexico dependence on oil price. The Mexican government decided to eliminate many import tariffs on various food products and, in 1987, this liberalization was extended to cosmetic products, plastic products, footwear, among others. By mid-1988, Mexico reduced most trade barriers by 20 points compared to 1985 (Moreno, 1999). After many months of negotiation, NAFTA came into force on January 1, 1994. The three countries decided to eliminate their tariffs, although Mexico in particular opted for a phase-out strategy, as it maintained some restrictions in sectors such as agriculture, oil and automotive. Obviously, each country had a different interest when signing the NAFTA. Mexico wanted to increase its exports to two industrialized countries and, at the same time, increase FDI. In contrast, the United States and Canada had other interests. United States saw the possibility of extending and ensuring the supply of its market both north and south. Nonetheless, at the beginning Canada did not want to participate in the NAFTA negotiations, it decided to be part of the largest market in the world, with almost 300 million inhabitants.

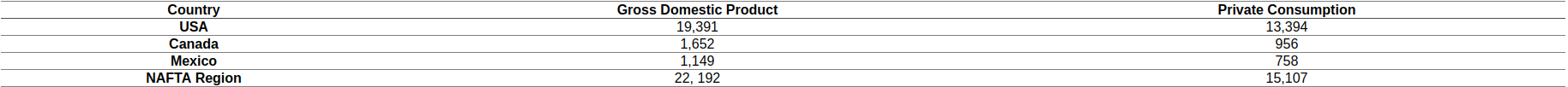

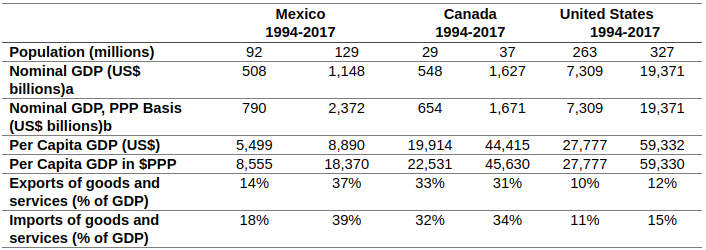

Compiled by CRS based on data from Economist Intelligence unit (EIU) online database.a Nominal GDP is calculated by EIU based on figures from World Bank and World Development Indicators.

Some figures for 2017 are estimates.

b PPPPPP refers to purchasing power parity, which reflects the purchasing power of foreign currencies in U.S dollar

Export-led growth

Inspired on the benefits of international trade, Hume (2015) argued: I shall…venture to acknowledge, that, not only as a man, but as a British subject, I pray for the flourishing commerce of Germany, Spain, Italy, and even France itself (on Jealousy of Trade, 1752), based on this statement, the import-substitution has been replaced by the export-led growth by Mexico. According to the World Bank, almost 40% of Mexico’s gross domestic product depends on international trade (World Bank, 2020), the debt crisis forced Mexico to accept Brady Plan,which had a strong dose of “Mainstream Economics”.

From 1982 to 1993, the Mexican government started a program of privatization, as we can see the figure 2, almost 85% of State-Owned Enterprises has been privatized. This privatization strategy was one of the most important points of the Brady Plan.

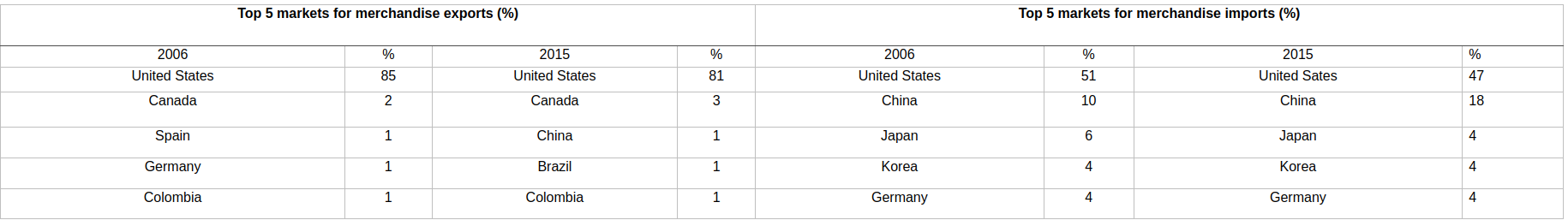

With the economic liberalization, Mexico has become one of the preferred countries to receive foreign direct investments to produce goods and services. The NAFTA agreement represents for Mexico the perfect way to ensure its export through two industrialized countries with the United States as the target market. It should be mentioned that 85% of Mexican exports go to the neighboring country, which represents an economic dependence, subject to any threat coming from the United States.

With this openness to international trade, Mexico has become an economy of export led growth. Mexico was particularly successful in the sectors such as: machinery, electrical and electronic equipment, transport vehicles, auto parts, among others. This has been due primarily to the policy of trade liberalization and also to less natural resources dependence.

In addition, Mexican export capacity not only depends on Mexico's commercial opening to international capital, but also on its geopolitical position, close to the world's largest market (which helps export companies reduce their inventory costs., among others), its world-class infrastructure, its low wages attractiveness for both skilled and unskilled workers.

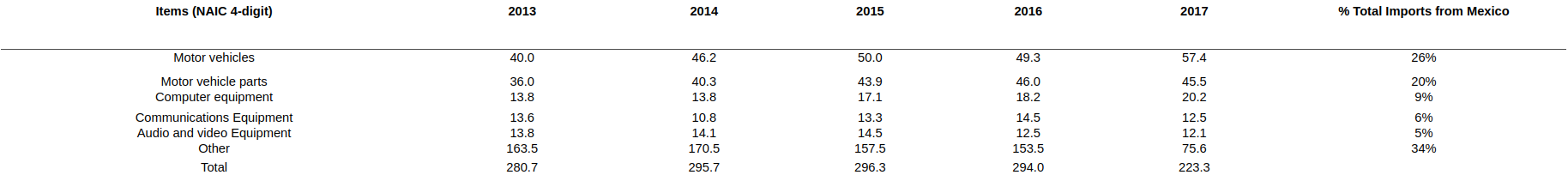

Congressional Research Service (2019)Nota Nominal US dollar. compiled by CRS using Interactive Tariff and North American Industrial Classification (NAIC) 4-digit level.

As we can see, the automotive sector is the most dynamic of the Mexican export to US. Mexico and the United States have a relationship of economic interdependence on one side and geopolitics on the other. In addition, it is important to point out that Foreign Direct Investment plays an important role in the economic relationship between NAFTA countries. The United States is the largest single investor in both Canada and Mexico, with a stock of FDI into Canada reaching $391.2 billion in 2017, up from a stock of $69.9 billion in 1993 and the stock of US. FDI in Mexico increased from $15.2 billion in 1993 to $109.7 billion in 2017 (CRS, 2019). However, according to the International Organization of Automobile Manufacturers (OICA), the automotive sector in Mexico produced 4,068,415 vehicles in 2017, which represents an increase of 13% compared to 2016.

The automotive sector exports have created more than 137,000 jobs in the last twenty-five years and have reached 118 billion dollars in exports in 2017. These statistics place Mexico as the seventh producer and the fourth world exporter of light cars. Also, according to ProMéxico data, in 2017 the automotive and auto parts industry contributed 3% of the Gross Domestic Product, which means that the automotive sector not only links Mexico with the most important production chain in North America, but also It is also an important source of foreign currency, which guarantees a stable exchange rate.

The renegotiation of NAFTA and the US Federal Immigration Law

The United States has the largest global trade deficit since 1975. Its deficit with countries meet at least one of the following three criteria:

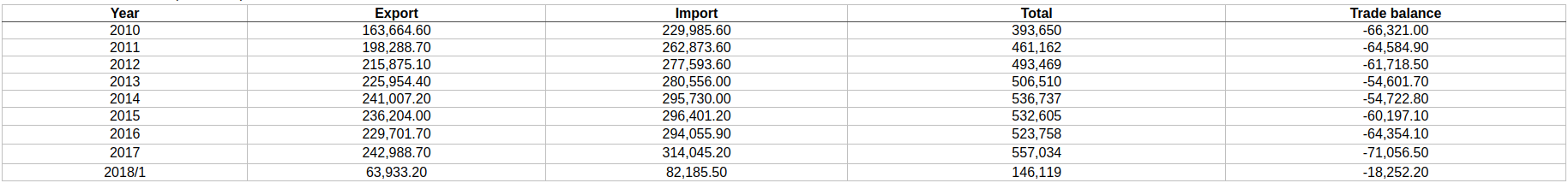

1.They can produce things at a lower price than the United States, such as consumer products or oil. That is changing with the production of shale oil in the United States. 2.They do not need what the United States has a competitive advantage. 3.They trade a lot with the United States, but the United States imports more than it exports. Most of the business partners with which the United States have deficits fall into the first two categories. The two largest are China and Japan. Some of the biggest deficits correspond to countries in the last category. They include Canada, Mexico and Germany (Amadeo, 2018). The trade deficit of the United States towards Mexico has been increasing in the recent years. What must not be forgotten is that the commercial and financial liberalization that currently contributes to the strength of Mexican exports to the United States was proposed by the US as the only solution that Mexico had to export goods and increase profits. When NAFTA came into force in 1994, the United States had a modest $1.3 billion trade surplus with Mexico. The following year, US began to experience annual trade deficits with Mexico. This is not only because the United States was flooded at that time with Mexican imports, but also because Mexico is one of the most resilient supply chains in the world. The US trade deficit with Mexico (26% of the total deficit trade) was unexpected, because when NAFTA was signed, Mexico was an economy based on both low wages and abundant endowment in work.

In that respect, the Trump Administration has reportedly justified its approach to trade negotiations by characterizing US free trade agreements (FTA) as unfair and detrimental to the economy, in part basing this conclusion on the size of bilateral and overall US trade deficits. The Administration also has reportedly characterized the trade deficit as a major factor in a number of perceived ills afflicting the US economy, including the rate of unemployment and slow gains in wages (Jackson, 2018).

As Inglehart and Norris (2016) noted, Trump used this trade deficit, not only with Mexico but also with other countries (like China) as the main element of his political agenda. It is useful to remember that the argument of Trump administration towards Mexico is based on four edges (so far): first, the deportation of around three million migrants; second, the construction of a border wall; third, reduction of the trade deficit with Mexico, which exists since when NAFTA was signed in 1994, and which has been increasing since 1998 (reaching 2016 to 61,7 billion dollars); and fourth, under the premise of creating jobs. President Trump tries to implement an anachronistic policy of repatriation of capital and investments from Mexico, specifically in the automotive industry, in which the United States lost its ability to compete. The first step of Trump Administration’s strategy had the support of some senators, not only putting tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico (the tariffs of 25 percent on steel imports and 10 percent on aluminum imports), but also, he announced a new merit-based immigration law known as RAISE (Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment) Act in order to reduce the number of legal and undocumented immigrants. The RAISE was introduced under the following terms:

Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment Act or the RAISE Act

This bill amends the Immigration and Nationality Act to eliminate the diversity immigrant visa category.

• The fiscal year limit for refugee admissions is set at 50,000.

• The President shall annually enumerate the previous year's number of asylees.

• The bill defines: (1) “immediate relative” as the under-21-year-old child or spouse of a U.S. citizen, and (2) "family-sponsored immigrant" as the under-21-year-old child or spouse of an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence.

• The worldwide fiscal year level for family-sponsored immigrants is reduced.

• The bill establishes a nonimmigrant alien W-visa for the parent of an adult (at least 21 years old) U.S. citizen (United States Senate, 2017).

With these measures, Trump administration is aimed at curbing illegal and legal immigration. Also, he tries to press through all possible avenues in the renegotiation of NAFTA. In addition, he sent a budget proposal to the US Congress of 7.7 billion dollars for the construction of the wall between the two countries, and Congress authorized just 1.3 billon (Bennet, Berenson & Abramson, 2019), which would lead to the militarization of the border.

The renegotiation of NAFTA has been carried out in a context of power and political economy. These two concepts represent the dimensions of political economy between both countries. The political economy today is defined as analysis that studies the linkages between politics and economics (World Bank, 2008). In this sense, the absence of the state capacity is one of the major problems of this Free Trade Agreement. It is important to note that there is a trade dependency between both countries, but this relationship is also characterized by the power imbalance. Thus, economic power arises from the capacity to interrupt economic relations (Hirschman, 1945). From this approach, we can highlight that power plays a crucial role not only in this specific case but also in any international relationship. Thus, Weak states, poor countries (Deaton, 2015).

Conclusion

The above analysis on immigration and trade demonstrates that what the Trump administration is really seeking is not to protect American wages and to create a transparent process for immigration to America through RAISE and new merit-based legal immigration system, but to apply tariffs on countries such as Mexico, Canada and China in order to reduce the US trade deficit and prioritize the interest of the big business.

The immigration policy of the Trump administration contrasts forcefully with the interests of the farm sector which places the issue of undocumented workers in the center of immigration debate. Due to the farm sector’s heavy reliance on undocumented workers and the difficulty of this work there is considerable turnover in the agriculture sector, many undocumented workers start working in agriculture but move on to other sectors as quickly as possible (World Agricultural Economic and Environmental Services , 2014). In addition, in sectors such as agriculture, immigration is not a problem, but a solution to prevent not only the increase in food prices, but also to ensure exports of agricultural products. This situation forces the agricultural sector to constantly hire many undocumented workers. Furthermore, from the point of view of orthodox trade theory, it is unfeasible to think of raising wages in the agriculture sector to attract American workers without increasing inflation. From this perspective, we can say that undocumented workers play a crucial role in the farm sector of the US. Thus, the US trade policy under the Trump administration to impose tariffs on all imported goods from Mexico, is to protect large US enterprises and to make the rich richer and, at the same time, reducing the purchasing power of the US consumers. Evidence continues to show that instead of reducing the flow of immigration, tariffs will have some negative effects on the US economy in the middle run and would make immigration flows to the United States even worse in the long term. Immigration does not create trade deficits in the US economy. Therefore, as tariffs are increased, both the rate of inflation and unemployment will increase in the US economy. In addition to this, it has been estimated that the US economy would lose $41.5 billion in GDP for each year the tariffs are in place (Egan, 2019). Thus, the idea that the US economy is strong enough to sustain its economic growth while tariffs will hurt only Mexico is an underestimation that US is Mexico’s largest export market, making the two economies closely intertwined. Thus, the immigration issue should be understood in this context in a political economic framework.

References

Álvarez, T. M. & Azpeitia Sánchez, F. (2010). Liberalización financiera y evolución del crédito en México. Denarius. Revista de Economía y Administración, 13(2), 57-108.

Amadeo, K. (26 July 2018). US Trade Deficit by Country, With Current Statistics and Issues. Why America Cannot Just Make Everything It Needs. The Balance. Retrieved from: https://www.thebalance.com/trade-deficit-by-county-3306264

Applebaum, A. (1 October 2018). Trump’s new NAFTA is pretty much the same as the old one - but at what cost? The Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/10/01/trumps-new-nafta-is-pretty-much-the-same-as-the-old-one-but-at-what-cost/?utm_term=.d55d6945bfd9

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (2018). Stats APEC. APEC. Retrieved from: http://statistics.apec.org/index.php/key_indicator/kid_result_flash/11

Atkinson, A. B. (2015). Inequality: What can be done. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bennet, B., Berenson, T. & Abramson, A. (2019). How Republicans Are Talking Trump Into Accepting a Smaller Border Wall Deal. Time. Retrieved from: http://time.com/5528673/donald-trump-congress-border-security-compromise-republicans/

Boswell , C. (2010). Addressing the causes of migratory and refugee movements: The role of the European Union. New issues in Refugee Research. Working paper No. 73. Institute for Peace Research. University of Hamburg Germany.

Clausing, K. (2019). Open: The Progressive Case of Free Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cohen, G. A. (1979). The Labor Theory of Value and The Concept of Exploitation. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 8(4), 338-360.

Congressional Research Service (2019). NAFTA Renegotiation and the Proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Deaton, A. (2015). Weak States, Poor countries. Social Europe. Retrieved from: https://www.socialeurope.eu/weak-states-poor-countries

Dougherty, J. E. & Pfaltzgraff, R. L. (1993). Contending Theories of International Relations. Buenos Aires: Pearson.

Egan, M. (5 June 2019). Tariffs on Mexico could cost America 400,000 jobs, a new report says. CNN Business. Retrieved from: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/06/05/business/mexico-tariffs-job-losses

Feagin, J. (2012). White Party, White Government: Race, Class and US Politics. New York: Routledge.

Gilpin, R. (2000). The Challenge of Global Capitalism. New Jersey: Princeton.

Girma, S., & Yu, Z. (2002). The Link between Immigration and Trade: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 138(1), 115-130. Retrieved from from www.jstor.org/stable/40440885

Guess, T. J. (2006). The Social Construction of Whiteness: Racism by Intent, Racism by Consequence. Critical Sociology, 32(4), 649-673.

Guillén, H. (1997). La contrarrevolución neoliberal en México. México: Era.

Harkinson, J. (27 October 2016). Meet the White Nationalist Trying to Ride the Trump Train to Lasting Power. Mother Jones. Retrieved from: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2016/10/richard-spencer-trump-alt-right-white-nationalist/

Hirschman, A. O. (1945). National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Holsti, K. J. (1964). The Concept of Power in the Study of International Relations. Background, 7(4), 179-194.

Hoppe, H. H. (1998). The Case of Free Trade and Restricted Immigration. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 13(2), 221-233.

Hume, D. (1758/2015). Essays: Moral, Political and Literary. New York: Wallachia Publishers.

Inglehart, R. F. & Norris, P. (August 2016). Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series. Retrieved from: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/trump-brexit-and-rise-populism-economic-have-nots-and-cultural-backlash

Inwood, J. (2019). White supremacy, White Counter-Revolutionary Politics, and the Rise of Donald Trump. Politics and Space, 37(4), 579-596.

Jackson, J. K. (28 June 2018). Trade Deficit and US Trade Policy. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45243.pdf

Kennan, George. F (1959). “American Diplomacy”. The University of Chicago. Printed in the United States of America.

Kissinger, Henry. A. (1957). A World Restored. Published by Echo Points Books & Media. Printed in the USA

Kregel, J. (2019). Globalization, Nationalism and Clearing Systems. EconStor. Public Policy Brief, 147. Retrieved from: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/201769/1/ppb_147.pdf

Kregel, J. (2004). External Financing for Development and International Financial Instability. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved from: https://unctad.org/en/Docs/gdsmdpbg2420048_en.pdf

Maskovsky, J. (2017). Toward the anthropology of white nationalist postracialism. Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(1), 433-440.

McKeogh, C. (2007). Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christian realism/Christian idealism. In W. D. Clinton (Ed.), The Realist Tradition and Contemporary International Relations (pp. 191-211). Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

Moreno-Brid, J. C. (1999). Reformas macroeconómicas e inversión manufacturera en México. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL.

Morgenthau, H. J. (1948). Politics Among Nations, the Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ocampo, J. A. (2014). The Latin American Debt Crisis in Historical Perspective. In J. E. Stiglitz & D. Heymann (Ed.), Life After Debt. International Economic Association Series (pp. 87-115). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ortiz, Martínez, G. (2003). América Latina y el Consenso de Washington. La fatiga de la reforma. Finanzas & Desarrollo, 40(3), 15-17.

Peters, M. E. (2017). Trading Barriers: Immigration and the Remaking of Globalization. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

ProMéxico (2016). The Mexican Aumotive industry: Current Situation, Challenges and opportunities. Ministry of Economy.

Sandoval, M. & García Arroyo, F. (1990). La economía mexicana en el fin del siglo. Revista de la CEPAL, Número 42, pp. 217-254.

Schaefer, J. & Baldas, T. (10 August 2019). Inside the El Paso shooting: A store manager, a frantic father, grateful survivors. USA Today. Retrieved from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/08/10/el-paso-shooting-survivors-recall-panic-terror-time-stopped/1974322001/

Spykman, N. J. (1942). America’s Strategy in World Politics. The United States and the Balance of Power. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Stiglitz, J. (2000). Globalization and its Discontents. Madrid: Taurus.

Strausz- Hupé, R. (1942). The Struggle for Space and Power. New York: G.P, Putnam’s Son.

Time Staff (16 June 2015). Here's Donald Trump's Presidential Announcement Speech. Time. Retrieved from: https://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018). World Investment Report. Retrieved from: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2018_en.pdf

United States Census Bureau (2020). Trade in Goods with Mexico. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c2010.html

United States Senate (13 February 2017). Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment Act or the RAISE Act. Retrieved from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/354

White, R. & Tadesse, B. (2010). Cultural Diversity, Immigration and International Trade: An Empirical Examination of the Relationship in Nine OECD Countries. In L. B. Kerwin (Ed.), Cultural Diversity: Issues, Challenges and Perspectives (pp. 775-808). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

World Agricultural Economic and Environmental Services (2014). Gauging the Farm Sector’s Sensitivity to Immigration Reform via Changes in Labor Costs and Availability. Retrieved from: https://www.fb.org/files/AFBF_LaborStudy_Feb2014.pdf

World Bank (2020). National accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=MX

World Bank (2008). Report No. 44288-GLB. Retrieved from: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/571741468336058627/pdf/442880ESW0whiBox0338899B01PUBLIC1.pdf

World Trade Organization (2020). Mexico and the WTO. Retrieved from: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/mexico_e.htm

Notes

Información adicional

Classification JEL: N7, P45