Artículos

Entendiendo la gestión del compromiso: la lealtad generacional en Perú

Entendiendo la gestión del compromiso: la lealtad generacional en Perú

Entendiendo la gestión del compromiso: la lealtad generacional en Perú

Cuadernos Latinoamericanos de Administración, vol. 17, núm. 32, 2021

Universidad El Bosque

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 27 Mayo 2021

Aprobación: 14 Junio 2021

Abstract: This study aims to determine the relevance of organizational commitment, well-being at work and work-life balance of employees according to their generational group. The objective is to determine which components of organizational commitment (proposed by Allen & Meyer (1991) are most relevant to the well-being of each group of employees belonging to a specific generational cohort. The study is based on the results of a questionnaire applied to more than 500 workers belonging to the three main generations: Baby Boomers, Generation X and Millennials. The employees included in this study work in commercial, industrial and service companies in Lima, Peru. The results show a close relationship between organizational commitment and well-being at work for the three generations. However, the greater significance in each generational group is different with millennials being predominantly normative commitment (sense of belonging, 0.242); while Generation X (happy to be part of the organization, 0.882) and Baby Boomers (happy to be part of the organization, 0.321) being predominantly affective commitment.

Keywords: Age Employee, Well-Being, Management, Organization Commitment.

Resumen: El presente estudio busca conocer la relevancia del compromiso organizacional, el bienestar en el trabajo y el balance vida-trabajo del colaborador según el grupo generacional en el que se encuentre. Se busca conocer los componentes que, dentro del compromiso organizacional (propuesto por Allen y Meyer (1991), son más relevantes para el bienestar de cada grupo de colaboradores pertenecientes a una determinada cohorte generacional. El estudio se basa en los resultados de un cuestionario aplicado a más de 500 trabajadores pertenecientes a las tres principales generaciones: Baby Boomers, Generación X y Millennials. Los empleados incluidos en este estudio trabajan en empresas comerciales, industriales y de servicios en Lima, Perú. Los resultados muestran una estrecha relación entre el compromiso organizacional y el bienestar en el trabajo para las tres generaciones. El compromiso normativo es el que tiene mayor influencia en las tres generaciones, destaca la lealtad que se desarrolla por el trato que la empresa le brinde al trabajador y sentido de pertenencia.

Palabras clave: edad del empleado, bienestar, administración, compromiso de la organización.

Introduction

The Peruvian population show a generational composition in the labour market that principally is made by Baby Boomers (2.8 million), Generation X (8.7 million) and Generation Y or Millennials (8 million) (IPSOS, 2019). Of this generational distribution, it is also mentioned that 48% of the Baby Boomer generation only has one job. As for Generation X, 84% work compared to the previously mentioned generation. As for the Millennials, like Generation X, 84% are working (INEI, 2019).

According to a study conducted by Transearch in 2013, most of the Peruvian companies were looking for generation X workers more than the other generations, it also revealed that 79% of the Peruvian executives, among managers, chiefs, and analysts, consider that generation X is the most attractive to have as collaborators in the Peruvian companies, so their search becomes more competitive.

Regarding commitment, although most executives (54%) stated that Generation X is the most committed to the development of the country, it is not necessarily so with their company, since the constant temptation of the competition makes it easier for them to change jobs (Transearch, 2013). Generation Y and X are less committed to the company than the Baby Boomers because the latter find it more difficult to get a job with the same level of payment and responsibilities.

It is due to this problem that the need to study, with more depth, the variables that influence the commitment of these three main generations arises. This study will seek to deepen the knowledge of the commitment for each generation, and thus, be able to identify the main variables that affect each of other. To do this, the age cohort was taken from different authors depending on the generation studied. In the case of the Millennials, it was taken as a basis the age cohort taken by Susaeta et al. (2013) in which they cover the age range of 27 to 44 years. For Generation X and the Baby Boomers, it was considered the authors Roberts and Manolis (2000) who take the age cohort of 45 to 56 and 57 to 75 years, respectively.

T1 Theoretical framework

T2 Generations

T3 Baby boomers

They are currently in their fifties and sixties and are defined by authors (Roberts & Manolis, 2000; O’Bannon, 2001; Smola & Sutton, 2002) as those born between 1946 and 1964. Still active in organizations and mainly in key decision-making positions for the company. This generation is characterized by its dedication and even addiction to work. Empowered and expecting the best from life, it is a generation concerned with the pursuit of status, loyalty, and quality of life (MacKay,1999).

This generation is now projecting itself towards the process of retirement from the labour market, some already retired, many interested in continuing to work after retirement, others in achieving a higher status through graduate degrees, and those experienced who apply their knowledge as consultants in different companies (Juergensmeyer & Anheier, 2017).

Hur and Hawley (2013) highlight the benefit that Boomers represent for organizations: the ability to use their experience and long-term vision in problem solving, eliminate negativism at work and negotiate better than their younger colleagues. While it is true that the younger generation stands out for its ability to work in teams and for its expert management of social networks, Boomers are an example of responsibility and reliability according to Juergensmeyer and Anheier (2017).

T3 Generation X

The Boomers, in average, are currently in middle and upper management positions. They were born between 1965 and 1974 (Roberts & Manolis, 2000; O’Bannon, 2001; Smola & Sutton, 2002). The X grew up in the shadow of the Baby Boomers (Zemke et al., 2013). According to the study by Smola and Sutton (2002), the values towards the work of The X differ significantly from those of the Boomers. They wonder what their benefit is in each job, and they strive to achieve their goals as well as those of the organization. They also found that they were less loyal to the organization and more focused on personal gain. However, the Generation X of today is a mature, well-prepared professional with responsibilities and who composes a large part of the labour market. They show characteristics such as those mentioned by Gross and Scott (2001), a generation for whom work is an essential part of their self-definition and that, while resisting the paradigm of corporate loyalty, values the recognition and feedback from their bosses, as well as the relationships with their colleagues within the organization.

T3 Generation Y

Generation Y or Millennials are those born in the early eighties and beginning of the 21st century. They have a different way of thinking and acting, which is why they attract so much interest among companies, as they have a strong work ethic, sense of responsibility and entrepreneurial behaviour (Tulgan & Martin, 2001). Thanks to globalization, the characteristics of this generation are more similar between countries than those of any other generation and have a natural aptitude for electronic communication (Stein, 2013; PWC, 2011). They need constant feedback and the possibility of personal and professional growth, and they are the generation least committed to the organization (Brusilow, 2008; Katz, 2008; Safer, 2007).

Millennials are an important part of the world’s labour market, many are entering or establishing themselves in leadership positions and some others are still practicing. According to Deloitte’s study (2014), Millennials express very little loyalty to their employers and are constantly thinking about leaving the company in search of new opportunities.

T2 Organizational commitment

In the business world, organizational commitment is known as the degree of dedication and attachment people develop towards the company where they work. Over the years the concept of organizational commitment has been well studied, since it is related to other variables associated to worker’s performance, to his or her intentions to leave or remain in the company, and to productivity.

One of the best-known approaches is analysed from the psychological point of view, is that of Meyer and Allen (1991) who emphasize that organizational commitment is a psychological state that characterizes employees’ relationships with the organization and have implications for their decisions to continue or stop working for the organization. They propose a multidimensional model to explain the organizational commitment, made up of three components: Affective, Continuity and Normative. The three main components of commitment named above will be described next.

T3 Affective commitment

It is the desire, on the part of the worker, to remain being a member of the organization because of an emotional bond with it. The author noted that workers who have an affective commitment identify with it, accept its goals and values, and are more willing to make extra efforts on behalf of the organization. There are certain antecedents that can influence affective commitment, such as personal characteristics, organizational structure, and work experiences. Personal characteristics determine whether and to what extent workers’ willingness to engage in affective commitment is generated (Meyer & Allen, 1991). For Mowday et al. (1982), the elements that influence the affective component are grouped into personal and organizational characteristics and experiences within the company.

T3 Normative commitment

Is a duty, on the part of a worker, to remain being a member of the organization due to a feeling of obligation. Abandoning the organization generates guilt (Colquitt et al., 2007). This commitment exists when there is a sense that staying is the right thing to do.

This feeling may correspond to personal work philosophies or general codes about what is good or bad. In addition to this, there seem to be two ways of building a sense of obligation into the commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1991). One is to make the employee feel that he or she owes something to the employer, so the former feels obliged to repay the employee with his or her commitment. Meyer and Allen (1991) refer to the role of parents and the culture in which a person operates, as well as reciprocity by obligation, as elements that influence a worker’s susceptibility to the normative commitment.

T3 Commitment of continuity

A worker’s need to remain a member of the organization due to concerns about the cost of leaving. Leaving the organization usually produces a feeling of anxiety. In this commitment there is a benefit associated with staying on the job and a cost associated with leaving. A high commitment of continuity makes it difficult for a worker to move to another organization because of the losses associated with a job change. One factor that increases this organizational commitment is the total amount that a worker invests (in terms of time, effort, energy, etc.) in fulfilling his or her duties in the organization, as well as the lack of employment alternatives. This type of commitment tends to create a much more passive commitment than the affective one, in terms of loyalty (Meyer & Allen, 1991).

Another aspect that this component considers is the possibility that the employee may get another job with favourable conditions for him/her. Thus, to the extent that he feels that his opportunities in the market are scarce, the commitment to continue will increase (Betanzos et al., 2006). Workers with a high commitment of continuity will remain in the organization because they need it (Vila, 2005).

T1 Methodology

T2 Data Collection

A survey was made based on questionnaires and scales that were proposed by Allen and Meyer (1991). For the survey, the items included in Jaros (2007) survey, which refers to Allen and Meyer’s model, are considered in the organizational commitment. On the other hand, in the section corresponding to personality traits (Big 5), the scale proposed by John, Donahue and Kentle (1991) is used. The survey was taken to commercial and service enterprises in Peru, this was anonymous, and the application ended in March 2018. As a result of this procedure, we collected 509 surveys.

T2 Measurement of variables

Since both models are used, it was decided to use a model of Ordinary Least Squares regression (OLS) with robust errors due to the qualities that our data have, the explanatory variables of the first model are “feel good in your job”, “work-life balance”, the five big personality traits and the control variables like sex (a dichotomic variable where 1 is male and 0 is female), age, married (a dichotomic variable where 1 is married and 0 is not married), children (a dichotomic variable where 1 is having children and 0 has no children), education, type of contract, time in the organization, the generational cohort variable (where the Millennials are omitted) and a constant to try to moderate those variables that can influence the results.

The variables of the “Big 5” which are Consciousness, Neuroticism, Agreeableness, Extraversion and Openness also functioned as control variables and have been placed in the estimation as independent variables. The dependent variable is the organizational commitment to the organization, which is presented as an index that was constructed using the following equation:

On the other hand, in the second model, the dependent variable is “feel good at work” and the independent variables that seek to explain the model are the components of organizational commitment presented according to Allen and Meyer’s classification (Allen & Meyer, 1991). Each variable collected, either for the index of organizational commitment or for the other variables, were on a Likert scale.

T2 Survey validation

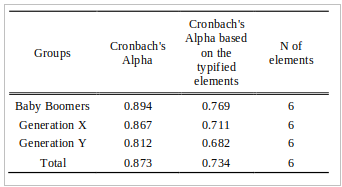

To validate the survey, a brief analysis of the psychometric properties of the instruments was carried out. For the reliability analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha statistic was used, which gives a measure of reliability for the variables that are related to a construct. With respect to the index of organizational commitment, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.873 in total, 0.812 in Generation Y, 0.867 in Generation X and 0.894 in Baby Boomers was obtained, as shown in Table 1, which accounts for the high reliability and internal consistency of the scale.

T2 Descriptive statistics

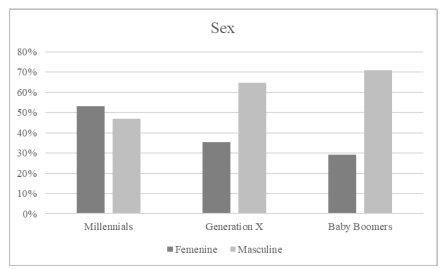

However, in the work-life balance, although the Baby Boomers remain the first in this variable with an average of 3.235, the Millennials are the ones that continue with 2.820, and, finally, Generation X with 2.790. In service time, the Millennials are the ones with the lowest average number of years, followed by the Generation X and finally the Baby Boomers. According to the sex of the sample, it can be seen in Figure 1 that in both Generation X and Baby Boomers, males predominate in comparison to females.

Descriptive statistics of the sample by sex

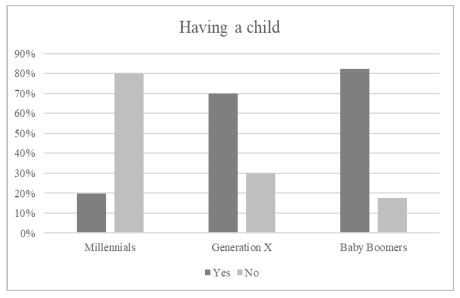

However, in the Millennials, women predominate according to the total number of respondents for this study. Having a child, as shown in Figure 2, shows that the Baby Boomers have on average more children than other generations, reaching more than 90%, and the Millennials have fewer.

Descriptive statistics of the sample by having a child

On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3, Generation X workers are those who, on average, assume more management positions than other generations by more than 60%.

Descriptive statistics of the sample by managerial position

T1 Results

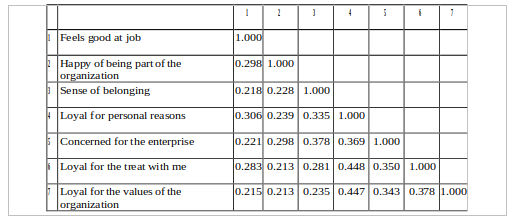

To eliminate the possibility of the existence of multicollinearity between the explanatory variables, a matrix of correlation between the independent variables is presented. The correlation matrix presented below is shown in Table 2. All the relationships are less than 0.5 and therefore there will be no problem at the time of making the empirical model.

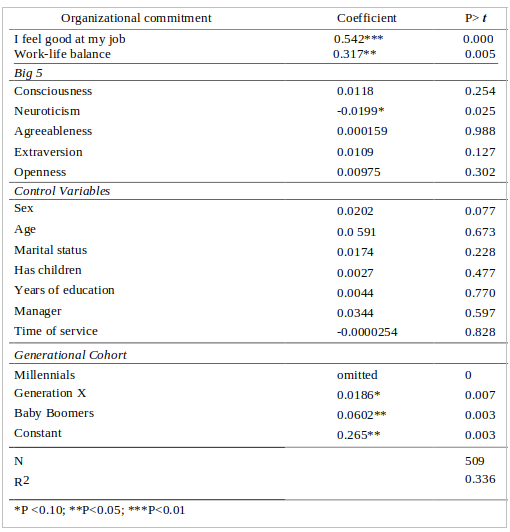

According to the results in Table 3, the positive feeling at work and the work-life balance play an important role in the commitment to the organization, the first variable being the most important. In addition, we can see that generational commitment is different depending on the type of generation in which it is found. Omitting the Millennials, we can conclude that the Baby Boomers are 0.602 times more committed than the Millennials and generation X is 0.01 times more committed. This leads to the conclusion that, within the three age ranges, those who are less committed are the Millennials, then the Generation X, and then the Baby Boomers.

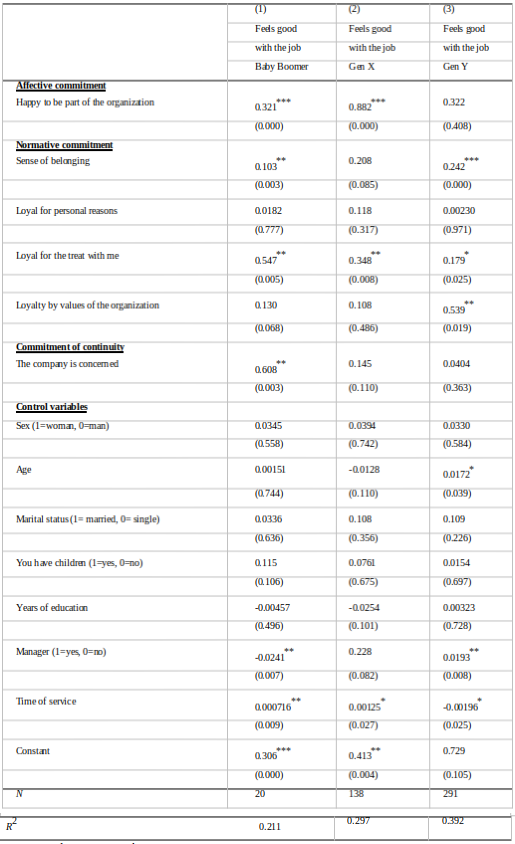

On the other hand, in Table 4, the variables of organizational commitment for the Baby Boomers, the affective organizational commitment represented by the variable “happy to be part of the organization”, has a significant value and helps to increase by 0.321 in the value of welfare with their work. With respect to the normative organizational commitment, “the loyalty for the treatment with the worker” and the “sense of belonging” take significant values, being the first one that has greater influence in the satisfaction of the worker with a 0.547. The commitment to continuity is also significant in this generation with the variable “I am concerned about the company”.

The affective commitment in The Generation X was significant and its influence on the labour welfare of the worker is greater than that of the Baby Boomers, being 0.882. The normative commitment shows only a significant variable which is “loyal for the treat with me”, which means that when this variable increases by one unit, the feeling of labour wellbeing will increase by 0.348. In this generation no variable of the continuity commitment is relevant.

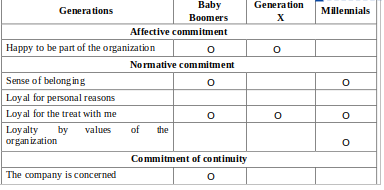

In the case of Generation Y, there is no significant variable for affective commitment. However, for the normative organizational commitment we have the variables “sense of belonging” with an impact of 0.242, “loyal by values” with an impact of 0.0539 and “loyal for the treat” with an impact of 0.179 significant in the order presented. Finally, the commitment to continuity shows no significance. As a summary of the above, Table 5 shows the variables of the commitment where the symbol “ꓳ” shows the variables that are significant in each generation.

T1 Discussion

Within the results, it can be observed that the organizational commitment takes an important role in the three generations, however, the intensity and significance is different for each of them. The Baby Boomers are the main ones to value this variable more, and this coincides with the characteristics studied previously, since this generation gives a great part of its life to work (O'Loughlin., Loh & Kendig, 2017). They are even willing to sacrifice family for work (Bridgers & Johnson, 2006; O'Loughlin et al., 2017). They are characterized by dedication to work, a quest for status, an improved standard of living, and an orientation to work as an anchor of life (Almeida, 2012).

In addition, the organizational commitment of continuity is what motivates them the most, which may be due to the need they have to stay in the company given their age and the difficulty they would have in getting a new job (Sodexo, 2018). As in previous studies on generational differences at work, it can be observed that the commitment to continuity is important because they value work (Parry & Urwin, 2017).

On the other hand, in Generation X, although their organizational commitment is also important for the well-being of the worker of this generation, it is superior to that of the Millennials but less than the Baby Boomers. This is because the appreciation of work is different since they consider it to be temporary and each company is a steppingstone to something better since they are at the peak of their careers and tend to have a greater number of jobs offers, especially for senior positions due to the experience already acquired (Filipczak, 1994; Parry & Urwin, 2017; Brown & Marston, 2018). In addition, compared to the Baby Boomers, they seek a balance between work and personal life (Chirinos, 2009;Cox, 2016), and would not be so willing to sacrifice work for their personal life. The affective commitment is what keeps them more comfortable at work, specifically the happiness they perceive from being part of the organization.

The Millennials are still not as motivated by organizational commitment as the two previous generations. This is because, despite seeking a work-life balance (Yeaton, 2008; Afif, 2019), they need more pleasure and fun at work (Molinari, 2011), as well as greater labour flexibility (Chirinos, 2009; Mihelič & Aleksić, 2017) and new opportunities, with varied positions at work (Deloitte, 2014). The normative commitment is what predominates in the motivation of this generation.

In addition to its strong work ethic that sets it apart from other generations (Tulgan & Martin, 2001; Claure & Böhrt, 2004; Chandan, 2019). With respect to loyalty, the Baby Boomers are the generation that most appreciates this variable, although for all three it is relevant. This is because this generation emphasizes the search for status and good treatment, in addition to being idealistic and, in generation X, loyalty is more oriented to the results that the company gives (Chirinos, 2009).

T1 Conclusion

For companies it is necessary to know the generational differences both in the characteristics of each generation and the factors that most motivate them to increase their organizational commitment. This is important, since the level of the indicators of organizational commitment is very similar, within the different levels of organizational commitment indicated in this study, a range of policies should be considered that are adapted to people according to their characteristics. This should be applied by providing independence so that people can find different options according to their needs. And, therefore, effective management of generational diversity will require successful managers to develop an understanding of the mindset of each of the different generations (Kogan, 2001; Farias, 2017). Managers will need to learn to flexibly manage their diverse team.

In the case of the Millennials, the normative commitment (loyalty by values of the organization) is the one that impacts more on their well-being at work. It is suggested that a greater number of opportunities be provided to be able to get involved in the work so that they can identify with the company, in addition to allow for involvement in projects that seek to help the community in some way such as improving the environment, and this according to Stein (2013), this type of activity coincides with contributing to the improvement of their community which they are happy to do. On the other hand, it is suggested to provide flexibility in work schedules because this favours the work-life balance so desired by them (Shagvaliyeva & Yazdanifard, 2014). In addition, this work flexibility so highly valued by Millennials (Randstad Work Solutions, 2007; Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), 2009; Simmons, 2008), will provide greater job satisfaction (Bauer, 2004) and job performance (Origo & Pagani, 2008; Ranaweera & Dharmasiri, 2016).

On the other hand, for Generation X (happy to be part of the organization), the affective commitment is the one that predominates with greater intensity so that the worker finds himself with a greater well-being at work. It is because of this that it is suggested to maintain the sense of belonging by building trust between collaborators and bosses, which can be done through a safe space of open communication since it strengthens the organizational commitment of the employees to their organization and helps to reduce the probability that they will seek new employment opportunities outside the organization (Meyer & Allen, 1997). In addition to carrying out activities that allow for the consolidation of collaborative relationships. These relationships will help to have a better work environment within their work centre (Hernández-Espallardo, Osorio-Tinoco & Rodríguez-Orejuela, 2018). In addition to generating a better performance, since relating with their colleagues, it will generate the learning synergy valued by this generation (Llorente-Alonso & Topa, 2019).

Additionally, leaders must motivate their team by showing them that what they do has a significant purpose in the company and that they are aware of that impact (Setiyani, Djumarno, Riyanto & Nawangsari, 2019). Especially in Peru, this generation is the one that most attracts the labour market and is placed in managerial positions (Transearch, 2013). Therefore, they must understand the generational differences and achieve the organizational commitment of the Millennials since it is the generation that has the greatest difficulty in understanding their needs at work.

Finally, the Boomers (the company is concerned) present as the most relevant factor the commitment of continuity. Therefore, it would be suggested to create a mentoring plan by this generation to train young employers who do not yet have enough experience for the position. This would also help to train their successors who will help the good functioning of the company (Beutell & Wittig-Berman, 2008; Fishman, 2016). This would help them feel useful in their work, which would generate job satisfaction among this generation (Kurniawati, Arisamadhi, & Wiratmadja, 2016). This job satisfaction will also support good job performance (Locke, 1970; Wright & Cropanzano, 2000).

Given the generational differences of the workers, this paper aims to contribute to the need to develop a variety of policies within the organization and to develop different management styles to encourage the organizational commitment of its workers. It is because of this that a transformational leadership style is suggested. This type of leadership has people as its central axis to achieve change in the company (Burns, 2004). Transformational leadership is based on the trust, respect, and admiration that employees feel towards the figure of more authority (Bass, 2009). This would help to meet the needs of each type of worker and thus improve their well-being since this type of leader is characterized by empathy and the ability to communicate easily with them, which helps to promote their participation.

According to this type of leadership and since loyalty is an important variable for commitment, it is necessary to create spaces in which the employee feels that he/she is important to the company. To do this and to know the needs of workers, it is necessary to build trust with them. This trust is generated mainly by the sincerity and clear norms that the company shows (Omar & Urteaga, 2008). According to this, the transformational leader must not only gain the trust of his employees by promoting direct communication to generate an effective approach but must also demonstrate the trust he has in his collaborators and an equitable treatment and a recognition to the result and effort of each one of its workers (Peng, Lee & Lu, 2020). In this way, leaders will be able to promote loyalty, which our results show as one of the most important variables for all generations.

In line with all this, it is encouraged, to a future study, to continue investigating the new reality and how it has changed in the remote work. It would be very interesting to know the aspects that have changed over the generations, but also, it is recognized as a limitation of this study that due to the non-existence of databases in Peru on commitment, the study group was limited. Also, not all types of organizations at different years were included, which does not allow us to make conclusions in a general way.

References

Afif, M. R. (2019). Millennials Engagement: Work-Life Balance Vs Work-Life Integration. Social And Humaniora Research Symposium, 1-2.

Bass, B. M. (2009). The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, And Managerial Applications. Simon And Schuster.

Bauer, T. (2004). High Performance Workplace Practices and Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Europe. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1265.

Brown, J. & Marston, H. (2018). Gen X And Digital Games: Looking Back to Look Forward. In International Conference on Human Aspects of It for The Aged Population (pp. 485-500). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92037-5_34

Burns, J. (2004). Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press.

Claure, M. & Böhrt, M. R. (2004). Tres dimensiones del compromiso organizacional: identificación, membresía y lealtad. Ajayu Órgano De Difusión Científica Del Departamento De Psicología Ucbsp, 2(1), 77-83.

Chandan, H. (2019). Technology, Learning Styles, Values, And Work Ethics of Millennials. In Advanced Methodologies and Technologies in Business Operations and Management (pp. 892-903). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2255-3.ch378

Chirinos, N. (2009). Características generacionales y los valores. Su impacto en lo laboral. Observatorio laboral revista venezolana, 2(4), 6.

Cox, L. V. (2016). Understanding Millennial, Generation X, And Baby Boomer Preferred Leadership Characteristics: Informing Today’s Leaders and Followers. Dissertation, 42. https://bit.ly/3zRSFbl

Fishman, A. (2016). How Generational Differences Will Impact America’s Aging Workforce: Strategies for Dealing with Aging Millennials, Generation X, And Baby Boomers. Strategic HR Review, 5-8.

Gauthier, M. (1999). Dispersive Xas at Third-Generation Sources: Strengths and Limitations. Journal Of Synchrotron Radiation, 6(3), 146-148.

Hur, H. & Hawley, J. (2013). Turnover Behavior Among Us Government Employees. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318823913

Hernández-Espallardo, M., Osorio-Tinoco, F. & Rodríguez-Orejuela, A. (2018). Improving Firm Performance through Inter-Organizational Collaborative Innovations: The Key Mediating Role of the Employee’s Job-Related Attitudes. Management Decision, 56(6), 1167-1182. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-02-2017-0151

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI) (2019). Características de la Población. INEI. Reporte de base de datos realizada en Perú.

Ipsos (2019). Generaciones en el Perú. https://www.ipsos.com/es-pe/generaciones-en-el-peru-2020

Kurniawati, A., Arisamadhi, T. M. A. & Wiratmadja, I. I. (2016). Relationship Among Individual Factors, Knowledge Sharing, and Work Performance: A Model from Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y Perspective. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 6-10). IEEE.

Locke, E. A. (1970). Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Theoretical Analysis. Organizational behavior and human performance, 5(5), 484-500.

Llorente-Alonso, M. & Topa, G. (2019). Individual Crafting, Collaborative Crafting, and Job Satisfaction: The Mediator Role of Engagement. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 35(3), 217-226.

Mihelič, K. K., & Aleksić, D. (2017). “Dear Employer, Let Me Introduce Myself”–Flow, Satisfaction with Work–Life Balance and Millennials’ Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 29(4), 397-408.

O’Loughlin, K., Loh, V. & Kendig, H. (2017). Career Characteristics and Health, Wellbeing, and Employment Outcomes of Older Australian Baby Boomers. Journal Of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32(3), 339-356.

Omar, A. & Urteaga, A. F. (2008). Valores personales y compromiso organizacional. Enseñanza e investigación en psicología, 13(2), 353-372.

Origo, F. & Pagani, L. (2008). Workplace flexibility and job satisfaction: some evidence from Europe. International Journal of Manpower, 29(6), 539-566. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720810904211

O'bannon, G. (2001). Managing Our Future: The Generation X Factor. Public Personnel Management, 30(1), 95-110.

Parry, E. & Urwin, P. (2017). The Evidence Base for Generational Differences: Where Do We Go from Here? Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 140-148.

Peng, X., Lee, S. & Lu, Z. (2020). Employees’ Perceived Job Performance, Organizational Identification, And Pro-Environmental Behaviors in The Hotel Industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102632

Ranaweera, C. & Dharmasiri, A. S. (2016). Generation y and their job performance. Sri Lankan Journal of Management, 21(1), 39-82.

Randstad Work Solutions. (2007). The World of Work 2007. https://bit.ly/3rO0Xy9

Roberts, J. A. & Manolis, C. (2000). Baby Boomers and Busters: An Exploratory Investigation of Attitudes Toward Marketing, Advertising, and Consumerism. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(6), 481-497. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760010349911

Shagvaliyeva, S. & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). Impact of Flexible Working Hours on Work-Life Balance. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 4(19), 42311. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2014.41004

Simmons, K. S. (2008). Intergenerational Communication in the Workplace. The Online Journal for Certified Managers.

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) (2009). The multigenerational workforce: Opportunity for competitive success. https://bit.ly/3rBbOv2

Sodexo Perú (2019). 9 factores que buscan los trabajadores millennials en un empleo. https://bit.ly/3x9ujrD

Smola, K. & Sutton, C. D. (2002). Generational Differences: Revisiting Generational Work Values for The New Millennium. The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational And Organizational Psychology And Behavior, 23(4), 363-382.

Susaeta, L., Pin, R., Idrovo, S., Espejo, A., Belizón, M., Gallifa, A. Aguirre, M. & Ávila, E. (2013). Generation Or Culture? Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal. 9-10.

Transearch (2013). Empresas buscan más a generación X a pesar de su menor compromiso. https://bit.ly/3eYFRb2

Wright, T. A. & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Psychological Well-Being and Job Satisfaction as Predictors of Job Performance. Journal of occupational health psychology, 5(1), 84.

Zemke, R. & Filipczak, B (2013). Generations At Work: Managing the Clash of Boomers, Gen Xers, and Gen Yers in the Workplace. American Management Association